'You start to feel you're being rejected'

The face of unemployment in Murray Bridge is changing. This mum's story is one example.

This story was originally published behind Murray Bridge News’ paywall. Paywalled stories are unlocked four weeks after publication. Can’t wait that long? Subscribe here.

Crunch time has arrived for Natalie Anderson and thousands of other Murray Bridge residents.

Government payments which increased by $550 per fortnight in April, soon after COVID-19 restrictions came in, have dropped back down by $300 from this week.

For people like Ms Anderson – a mum and a long-term Jobseeker recipient – that means the economic crisis is beginning to bite.

The $550 coronavirus supplement had enabled her to buy a few things for her son, she said, and to pay off her electricity bill in two instalments instead of going onto a payment plan.

She hoped the federal government would not go through with its plan to take the rate of Jobseeker all the way back down to $40 a day in December.

She also wished people would not be so quick to judge Centrelink payment recipients.

“A lot of people don’t think we should get it – people think we shouldn’t be paid at all, that we’re just lazy – but I think that’s not very nice,” she said.

“So many people have lost their jobs this year and a lot of them have got mortgages, a lot of them are going to be losing their homes.

“How would you feel if it was you who lost your job and was in that situation?”

Ms Anderson wound up on Newstart, as it was then called, seven years ago after she lost a carer payment she had previously been getting to look after her son, Kydan.

She counted herself lucky to have got into community housing instead of waiting 20 years for Housing SA, and to have local service providers like the Salvation Army and AC Care for emergency relief and moral support.

She still hoped to find a job someday, but spending so long on the unemployment queue had been demoralising, she said.

“What’s difficult is you go out, ask anyone if they've got any jobs, and they say no,” she said.

“After a while you start to feel you’re being rejected, that you’re not wanted, even though they’re being very polite.”

Asked what message she would send to the politicians in Canberra, she invited them to walk a mile in her shoes.

“Instead of them getting pay rises all the time, why don’t they go homeless for a time or spend six months on the money we get and see what it’s like for them?” she asked.

Face of unemployed Australia is changing

While the stereotypical image of a job seeker is a school leaver who might be picky about what type of work they take on, Ms Anderson is closer to the reality.

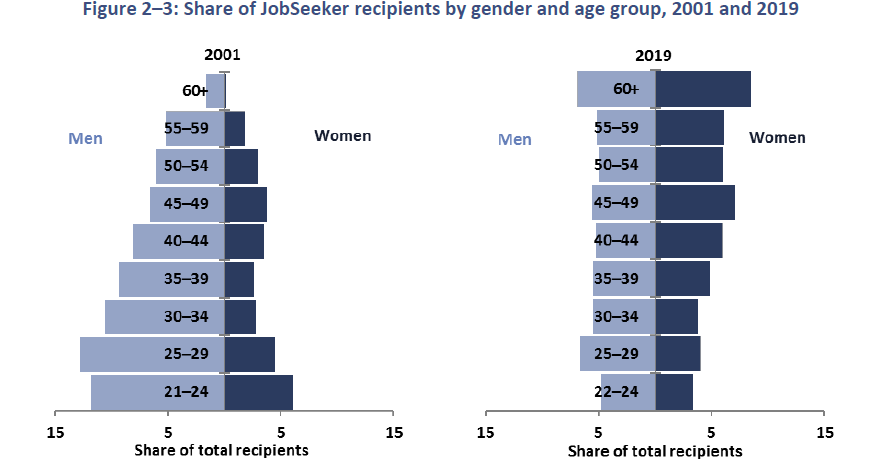

Most Jobseeker recipients are now people aged over 40, and a majority of those are women, according to a parliamentary report published last week.

More than one in seven people on unemployment benefits is aged over 60.

That’s seven times as many as there were at the turn of the century.

The changing profile of job seekers could be explained partly by changes to other payments, the report suggested.

More and more people on the unemployment queue had been diverted away from disability pensions or parenting payments, or were waiting to receive an age pension.

This week’s federal budget allocated billions of taxpayer dollars to solving unemployment.

But much of that funding went to programs targeting young people: wage subsidies for businesses that hire new workers aged between 16 and 35, and for those that put on new apprentices.

Other programs will help job seekers who need to improve their literacy and numeracy, mothers preparing to re-enter the workforce, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners who need to return to work upon their release.

Certain groups of people are not getting help they need, relief worker says

Renee, an emergency relief worker in Murray Bridge, said a succession of disasters – the global financial crisis, the drought, bushfires, the pandemic – had left whole sections of the community living in poverty.

She named three main groups:

- Older people whose superannuation had been hit hard by the global financial crisis of 2007-08, then low interest rates, and who could not yet get the age pension

- People who had previously received parenting or disability payments, who struggled to find work to suit their family circumstances or physical capabilities

- Non-citizens, who were not eligible for Centrelink payments

“People who could retire in a few years now can’t,” she said.

“Then you’ve got people on Jobseeker, people who can’t work, or who have less of a chance of getting that opportunity to work ... they’re (stuck) sitting there doing nothing, or doing volunteer jobs they don’t want to do, or getting rejected over and over again.”

All those barriers affected people’s mental health, she said, as they started to think they were too old or not good enough to get a job.

The low rate of Jobseeker payments – below the poverty line, prior to COVID-19 – did not help either, she said.

“People have to pay rent, put petrol in the car, buy clothes, get haircuts and attend job interviews, and on that payment it’s simply impossible,” she said.

“How do you choose between your health and food?

“How do you choose between electricity and food for your kids?

“If there’s no electricity, they can’t cook; if they have no phone, they can’t get a job; then they’re at risk of having their children taken away because it’s neglect.

“They shouldn’t have to make these choices.”

Help is available

- Get help with the basics: Murray Bridge Community Centre, call 8531 1799 or visit 18 Beatty Terrace; Murray Bridge Salvation Army, call 8531 1133 or visit 1 Fourth Street; AC Care, call 8531 4900 or visit 29 Bridge Street, Murray Bridge.

- Get help with mental health: Lifeline, call 13 11 14; Beyond Blue, call 1300 224 636; Headspace Murray Bridge, call 8531 2122 or visit 3-5 Railway Terrace.

- Find a local service for your needs: murraymallee.servicesdirectory.org.au.

Photo: Peri Strathearn. Image: Parliamentary Budget Office.