Why are there so many empty homes in the Murraylands?

We investigate a huge but hidden issue, asking why as many as 1500 local homes are vacant during a housing crisis and what can be done about it.

This story is now free to read. Help Murray Bridge News tell more stories like this by subscribing today.

The afternoon breeze blows right through a stone cottage in the heart of Murray Bridge whose windows and doors are all missing.

You can stand in the street and see right through to the backyard.

The cottage, built in 1930, is what a real estate agent might charitably describe as a fixer-upper: there are a few cracks and missing floorboards, and there doesn’t appear to be a pane of glass or fly screen left in the place.

It last sold for $95,000 four years ago and, considering how quickly local property values have risen since then, realestate.com.au estimates that it might be worth something in the high $200,000s today.

But right now, nobody lives there.

Several nearby residents told Murray Bridge News it had been empty for years.

On its own, that is hardly newsworthy – after all, every landlord clearly has a right to do whatever he or she wants with a private property.

But in the bigger picture, this house and others like it are representative of a significant issue around the Murraylands.

Roughly one in 10 houses in the Murray Bridge district – somewhere between 800 and 1500 of them – is vacant at a time when hundreds of local families have nowhere to live, and when new home builders are struggling to keep up with demand.

At a regional level, that was a problem, said Ross Womersley, chief executive of an organisation which campaigns for justice, opportunity and shared wealth for all: the SA Council of Social Service.

“We know, not just in Murray Bridge but across the regions, there has been this growth in homelessness in the last few years, in a huge part driven by the lack of secure and reasonable quality accommodation for people,” he said.

“We’re in a circumstance as a community where we have far too many people who cannot find somewhere to live that’s safe and affordable.

“Where we do have empty properties, we absolutely should be looking to understand whether or not they ... could be turned into good, affordable accommodation.

“In a place like Murray Bridge … (even) people on moderate and reasonable incomes who have jobs in the region can’t locate affordable housing.”

Murray Bridge News put two questions to three civic leaders, an accountant and a real estate agent:

- Why might so many houses be vacant?

- What can be done about it?

We also knocked on the doors of several reportedly empty houses to ascertain the facts for ourselves...

Why would someone leave a house vacant?

Some of Murray Bridge’s empty homes would be shacks, used by their owners for an occasional holiday; about 40 of them are available as holiday rentals on AirBNB.

Others might be empty because their owners are away on holiday, perhaps doing the grey nomad thing.

Some might be halfway through a renovation, or not fit to be lived in, though it would be hard to estimate exactly how many.

But is there any reason someone would choose to leave a property vacant for a long period, instead of renting it out or selling it?

Accountant Shaun Williams suggested there was no particular financial benefit to leaving a house empty, especially if you were still repaying a mortgage.

“If you owned the house you wouldn’t just abandon it because ... the value would be coming down, especially if someone broke in or someone’s squatting or whatever,” he said.

Housing prices were the highest they had ever been, and the current housing shortage meant that rental returns would be high – perhaps 5-6 per cent of a property’s value per year, instead of the 3-4% owners would have got a few years ago.

“It just doesn’t make sense to abandon a house that you own,” he said.

“If you left it empty for five years, what it grew by compared to what you rent, you get more rent than what it (grows by).

“There’s no tax hacks.”

Both he and real estate agent John DeMichele suspected that many of the empty houses would have to belong to the SA Housing Trust, but the statistics disagreed – more on that in a moment.

Private owners might leave a house empty for any number of personal reasons, Mr DeMichele said, like if they had needed to move away for work.

They might prefer not to rent a place out, or get family or friends to look after it; and they might fear the idea of selling it and getting stuck without a home of their own if prices kept rising.

“A home is gold at the moment,” he said.

“At the end of the day there’s no advantage.”

Murray Bridge Mayor Wayne Thorley suspected many of the houses which sat empty in the community belonged to the families of residents who had died, and who might spend years settling ownership or deciding what to do.

Landlords also lived in fear of tenants who might damage their properties and cost them money, he suggested.

Perhaps some houses had fallen into disrepair and their owners couldn’t afford to fix them up, federal MP Tony Pasin speculated.

How many empty homes are we talking about, anyway?

At the 2021 census, the Australian Bureau of Statistics estimated that there were 811 unoccupied homes in the Murray Bridge district.

Given the timing, that number could have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, or even the aftermath of the 2018 Thomas Foods fire.

But earlier this month, real estate analysts PropTrack suggested it was not an outlier.

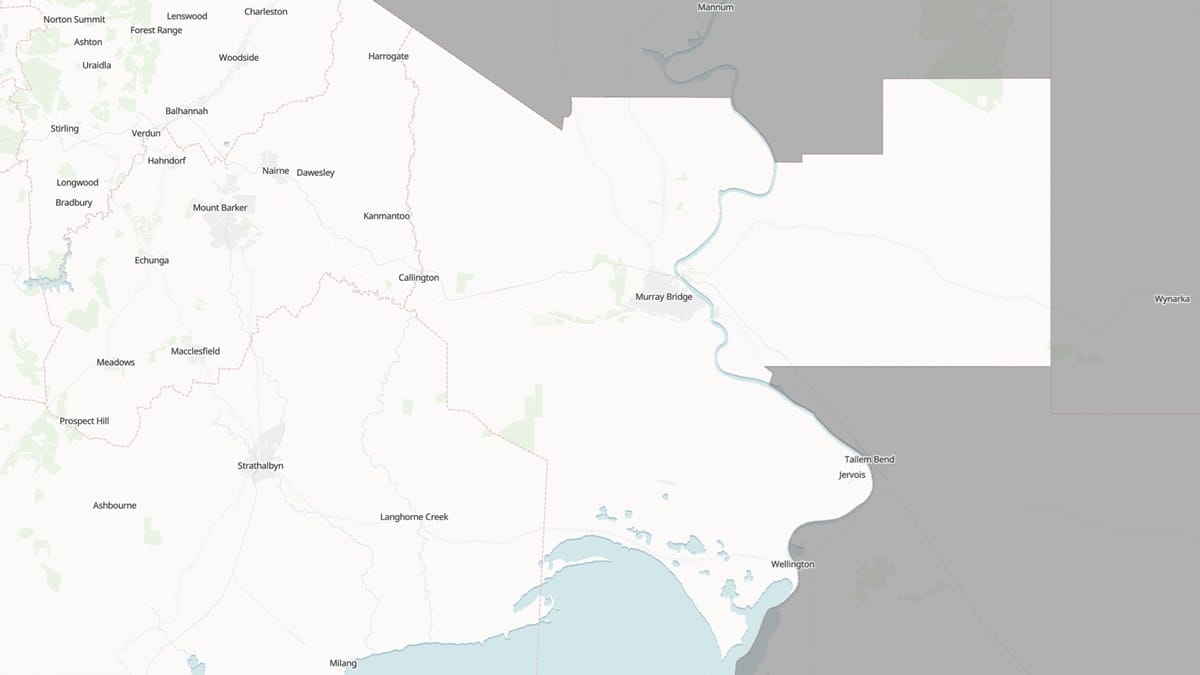

They estimated there were 780 empty homes in Murray Bridge and its suburbs, 320 at Mannum, 150 across both sides of Wellington, 126 at Tailem Bend, and dozens more elsewhere in the Murraylands – almost 1500 in all.

The state government’s Greater Adelaide Regional Plan landed in the same ball park last month.

Of the Murray Bridge district’s 10,406 dwellings, it said, 1315 were unoccupied – enough to house more than 3000 people.

The numbers would include holiday shacks, houses which had been vacated for renovations, those declared structurally unsound and those which were between tenants.

But not many of them belong to the SA Housing Trust, which told Murray Bridge News that – as of September 30 – just 38 out of its 629 Murray Bridge properties were vacant.

Twenty of those were being repaired, nine were under offer and nine were available.

In the neighbouring Mid Murray and Coorong districts, 64 out of 65 Housing Trust properties had tenants.

Could more of the region’s privately owned homes be made available, then?

Some of the houses Murray Bridge News visited were clearly empty, but others showed signs of being lived in, or done up. Photos: Peri Strathearn.

Murray Bridge News went to a community Facebook group to ask locals for tips about vacant homes around the community.

After fielding a number of suggestions, we visited half a dozen addresses to try to assess whether the houses that looked empty were, in fact, empty.

One home was fenced off, with a boarded-up front door, clearly unused; a neighbour speculated about a family dispute, and recalled having seen squatters in there.

A second home on a prominent street was occupied only by pigeons.

A third, in Murray Bridge’s west, looked run down and had a letter taped to the front door, addressed to “the occupier”; but a rear light was on.

A trio of units which had been vacant for 4-5 years, according to a nearby resident, showed signs of being renovated.

Do you know more about this story? Contact the author at peri@murraybridge.news or on 0419 827 124.

But not every tip-off proved accurate.

One place, with closed roller shutters and two cars on blocks in the driveway, had someone emerge from around the back; and another was occupied by an older gentleman who said he simply preferred to keep to himself.

Not all empty-looking houses are created equal.

But there are clearly a number around the community which are vacant and could, with a little TLC, be made liveable again.

Could policy changes could help us make better use of the housing we've already got?

The Victorian government made headlines in 2018 when it introduced a tax on vacant residential land, one which will apply across the whole state from January 1.

A tax of one per cent of the property’s value will apply to any property which is not used as:

- A residence for at least six months of the year

- A worker’s home-away-from-home for at least 140 days, or

- A holiday home for at least four weeks

Similarly, a “bed tax” – on unused bedrooms – could prompt more people to think about downsizing, Mr Womersley suggested.

Others have taken a more aggressive approach.

Victorian activist Jordan Van Den Berg is among those who have advocated publicly for squatters to take adverse possession of properties which have been vacant for a long period.

Laws vary from state to state, but generally speaking, if someone can demonstrate that they have had control of a property for a long period – 15 years in South Australia – they can attempt to claim legal ownership of it.

At least one such case succeeded in New South Wales in 2018, netting a property developer a $1.4 million home.

At a national level, though, changes to contentious policies like capital gains tax and negative gearing have been more popular in recent political conversation.

When you sell something, any profit you make – or “capital gain” – should theoretically be taxed at the same rate as your ordinary income.

But if the thing you sell is an investment property, you get a 50 per cent discount on that tax bill.

Negative gearing is when you make a loss on an investment property – for example, if you leave it empty and don’t make any income from it.

The law allows you to claim that loss as a tax deduction, again reducing your tax bill.

Both policies are straightforward enough, but in effect – according to analysts at the Australia Institute – most of the benefit goes to the very rich, costing the government revenue that could be used to help all Australians.

Changing those policies was at the top of Mr Womersley’s wish list.

“Negative gearing and capital gains tax … (treat) the housing market as an investment instrument rather than creating housing for homes,” he said.

“This is what has evolved, not that it would have been intended when those tax incentives were put in place, but as a consequence.

“We all should have a right to a home that is safe and secure, to have a roof over our heads, let alone one that is prepared for climate change so that you’re not spending a fortune keeping it cool in summer and warm in winter.”

It was also imperative that the state government invest in more public and social housing, he said.

The government had committed to building hundreds of houses per year, but it needed to build thousands.

Are any of those solutions worth exploring?

Federal MP Tony Pasin said he was surprised to learn that hundreds of homes were lying vacant in Murray Bridge, and he would be keen to understand why.

“If you had said to me 100 to 200 (houses were vacant), I’d say, well, that’s probably the norm, it’s what you would expect; but 700 is a substantial percentage,” he said.

At a national level, the housing market had a number of issues, he said: immigration outpacing the supply of housing, difficulties in accessing finance and finding builders, and long delays in getting a new home approved.

It was hard to be sure which of those issues was most affecting the Murraylands, but there were things a federal government could do.

“The solution to the housing crisis is to free up supply … and make sure the planning approvals are quick,” he said.

State MP Adrian Pederick argued that the Housing Trust needed to lift its game and repair any uninhabitable houses on its books.

More public housing was needed too, he acknowledged: “The lists are long for public housing and there can be many years’ wait, even on category one.”

But there was also a need for privately owned properties to be renovated and made available to tenants.

“I think there’s an opportunity for people to make investments or rebuild them,” he said.

“There’s been a lot of ongoing expansion in Murray Bridge, but it’s going to take a long time for those housing projects to be developed.

“There’s a bright future, (but) it doesn’t help people immediately.”

Mr Thorley said there was not much local governments could do to fill empty houses, aside from repossessing them if their owners failed to pay their council rates for many years.

It was rare, but it did happen – the council had seized two houses and one vacant lot this year, he said, including a property at Rockleigh where the rates hadn't been paid for 40 years.

He didn’t want the council to charge a higher rate against vacant properties, or step in and build houses; it was better to leave that stuff to Habitat for Humanity and AC Care.

Mr DeMichele suggested that the state government sell off more of its old public housing stock so that private developers could take over.

But in his opinion, filling vacant properties was a secondary issue; finding ways to build new houses more quickly would have a bigger impact.

“The biggest problem, I feel, is that the system that we’re in, between getting approval to build and construct to completion, it’s the time – it’s drawn out.

“We need to fix the system so that houses can be approved quicker and constructed quicker.

“There’s a lot of red tape in our society at the moment that slows the process ... therefore there’s a backlog of people waiting for homes.”

- Have your say: What do you think the solution is? Leave a comment below.