What is the First Nations Voice, and why is it important? Two Ngarrindjeri elders explain

Eunice Aston was on the stage in front of Parliament House on March 26, and Laurie Rankine was in the audience.

Locals support locals – that’s why this recent post is now free to read. Your support can help Murray Bridge News tell important local stories. Subscribe today.

At a significant moment in South Australia’s history, as Premier Peter Malinauskas fills in the paperwork that will create a First Nations Voice to speak for the state’s Indigenous people, Eunice Aston gives a huge thumbs-up.

The proud Ngarrindjeri woman was one of several local elders on the stage in front of Parliament House on Sunday, March 26.

There, too, was Aunty Ellen Trevorrow; and Uncle Moogy, Major Sumner, painted for a smoking ceremony.

From her vantage point, Ms Aston was overwhelmed by what she saw.

“I saw all the chairs (before the ceremony) and thought ‘there’s no way they’re going to fill all those chairs up’,” she said.

“Then people started rocking up.

“I expected opposition, but there was only a lone voice … there was the biggest mob supporting it.”

Laurie Rankine senior, the chair of Ngarrindjeri Ruwe Empowered Communities, described the passage of the First Nations Voice Bill as a massive step.

Keep in mind, he said, that only 70 years ago – within the lifetimes of elders living today – Indigenous people had been banned from towns around the Murraylands, forced to live in fringe camps on the outskirts.

Children had needed the authorities’ permission to go to school, and were told finishing year 12 would be a waste of time.

In his teenage years, playing at the Imperial Football Club, a coach had been fired for including him in a representative team.

The first time marchers crossed the old Murray Bridge for NAIDOC Week, they were heckled.

“What’s happening now, I never expected to see it in my time,” he said.

Explainer: How will the local, state and national voices work?

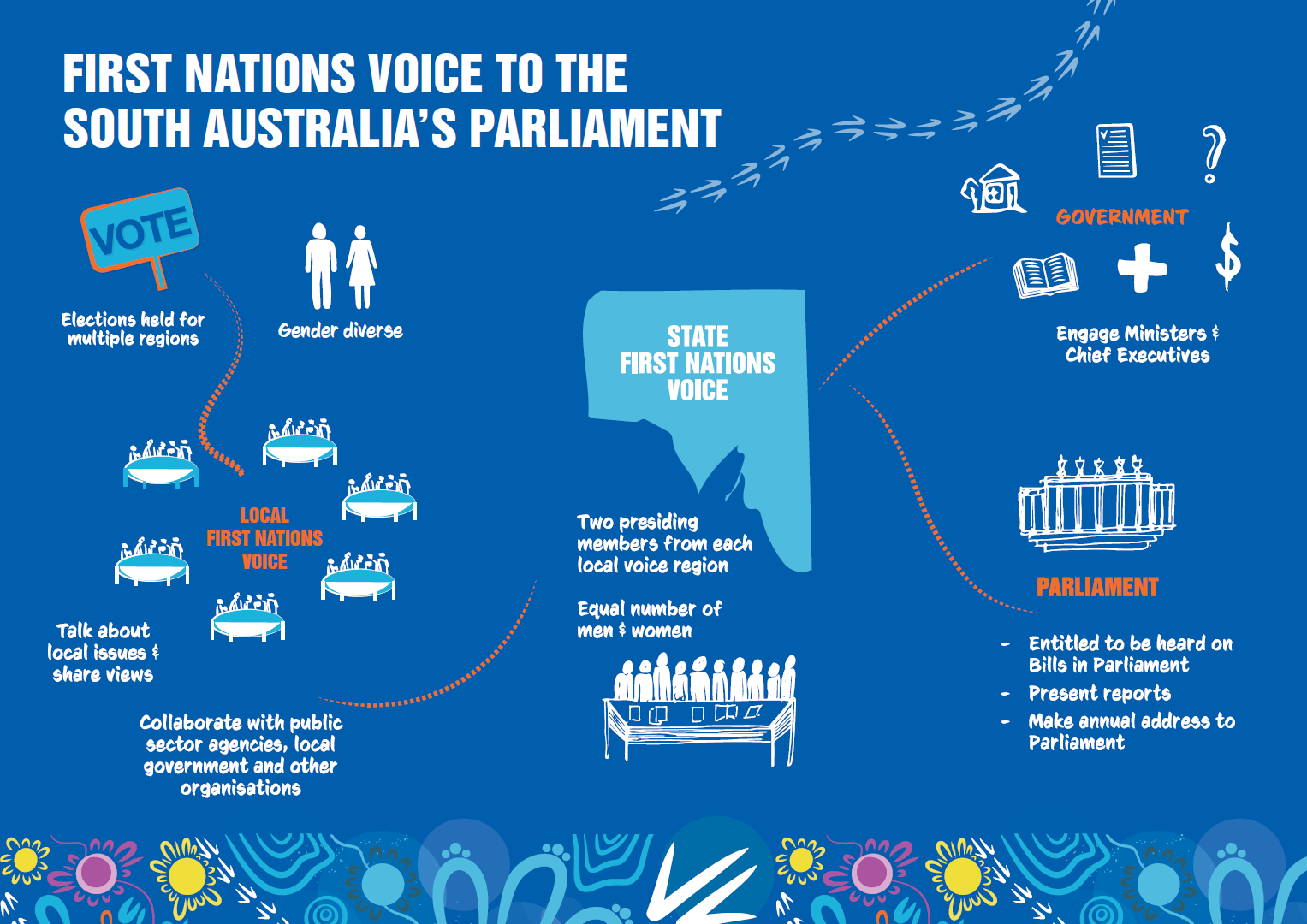

In simple terms, a Voice to Parliament is an advisory body whose members are elected by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Members of each Voice will have a direct line of communication with high-ranking members of parliament; and they will provide feedback whenever a government changes policies that will affect Indigenous Australians.

They will not pass laws, or veto them, or give out funding.

If this year’s national referendum gets up, there will be three levels to the Voice, like our three existing levels of government: regional, state and national.

The South Australian government has already passed laws which will create a state First Nations Voice, and regional Voices which will feed into it.

All Indigenous people living on Ngarrindjeri country, in the Murraylands, will be able to vote in elections for the Voice.

Representatives of our region will sit on a regional Voice alongside others from Meru, Peramangk, Ngargad, Bindjali and Buandig country: the Riverland, Mallee, South East, Adelaide Hills and Kangaroo Island.

In turn, that regional Voice will send two representatives to the 12-member state Voice.

The whole thing was designed in consultation with Indigenous people from around the state.

Meanwhile, in a referendum later this year, all Australians will be asked whether they support the idea of establishing a national Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice.

Like the state Voice, it would be included in the constitution, which would protect it from being changed or abolished by politicians.

For the national Voice to become law, it will need to be supported by more than 50 per cent of voters, plus a majority in at least four states.

The national Voice’s exact design would be finalised after the referendum, though a national consultation has already produced an exhaustively detailed proposal.

Why is a Voice to Parliament important?

The idea of a Voice to Parliament was one of three key demands made in the Uluru Statement from the Heart, a landmark 2017 declaration by representatives of almost every Indigenous nation in Australia.

Ms Aston was originally going to represent the Ngarrindjeri people at the summit where the declaration was made, but was unable to attend.

She hoped the regional, state and national Voices would help Indigenous people advocate for solutions for problems like overcrowded housing, issues with the foster care system, and short-term employment contracts.

In the big picture, though, the Voice was also a way Australia could move forward as a nation.

“This is a really good opportunity for Aboriginal people to be part of a foundation … so that we can establish what we want and where we’re going with it, but also to … help build the nation the way it should be: not built on anger, aggression, rejection,” she said.

“When I look at Australia the way it is, it’s a fractured nation.

“This is one of the ways to bring us all together.”

She had been sceptical of the voice idea at first, she said – after all, her people had been let down by the failures of ATSIC, the National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples and several other bodies over the past 50 years.

As Mr Rankine put it, “every time we get something that works for us, it gets shut down”.

And wasn’t it more important for a treaty to come first?

In time, though, Ms Aston decided that progress on any front was worth fighting for.

Besides, negotiations on that treaty between South Australia and the Ngarrindjeri people – started in 2016 but scuttled after the Liberal Party’s election to government in 2018 – are continuing in the background.

“For now, the only thing we’ve got is the Voice,” she said.

“This is the point where we can start solidifying some really good policies and conversations with government around things that can support Indigenous voices and sit alongside non-Aboriginal voices.

“It gives me a little bit of hope.”

- More information about the First Nations Voice in SA: www.agd.sa.gov.au.

- More information about the proposal for a national Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice: voice.niaa.gov.au.

- Read the Uluru Statement from the Heart: ulurustatement.org.